People of a certain age could be forgiven for not even knowing

who Mary Seacole is. She was a nurse (though the term is used loosely here and

she didn’t use it) who went to the Crimea to assist soldiers on the battlefield

at the same time that Florence Nightingale was achieving fame for her work in the

hospital at Scutari. She was notable for her determination: having been refused

the support of the War Office for the journey (perhaps because of her age; she

was approaching fifty) she raised funds herself for the voyage and established

a ‘British Hotel’ where casualties were treated.

|

| Mary Seacole's memoirs |

Mary Seacole was an amazing character to be admired for her

courageous career. But her importance in terms of lives she impacted on was comparatively

minor, and one would expect her to be almost forgotten – and certainly not

mentioned in primary schools. However, she made it into schemes of work related to the National Curriculum

from about 1992 because she was considered a black role-model, having been born

in Jamaica and being one-quarter black.

Certain educationalists of a non-critical bent then posed

the question, why was she not as famous as Florence Nightingale? Simple to say:

the contemporary white establishment must have been racist. Schoolchildren are

now solemnly taught by many teachers that the reason she’s not as famous as Florence

Nightingale is because she was black.

Obviously there are particular reasons for Florence

Nightingale’s enduring fame in comparison with Mary Seacole. Nightingale questioned

and challenged relentlessly, and tirelessly engaged with politicians and

royalty to ensure that not only military hospitals, but all hospitals followed the

hygienic practices necessary for them to be houses of healing rather than

slaughter. She is without question the parent of modern nursing, and deserves

to be famed then, now, and indeed as long as humans need healthcare.

|

| Nightingale's Notes on Nursing - the first book of its kind |

Consequently, as a minor character, Mary Seacole does not

need to be discussed at primary level, and the Government are right to be

questioning her status. However, you would be hard pressed to gain historical

perspective from the Independent’s report, which quotes the black campaigner

Darcus Howe as saying that the proposal to reduce her position in the curriculum

“is a punishment for the uprisings of summer 2011” (the expression “uprisings”

being what everyone else calls “looting and riots”).

Howe’s foolishness speaks for itself. But it is of more

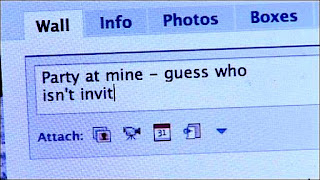

concern when the Independent tells us with its own voice that Mary Seacole “was

as famous as Florence Nightingale during her lifetime”. This is utterly

absurd, as this Google ngram shows (which computes all mentions in published

books from 1850 until the year of Seacole’s death).

(The blue line, if you can't spot it, is flatlining at the bottom.)

This controversy is not just about falsification of history, but about a wilful ignorance that the contribution of one human being to the world can be different in value from that of another. The Labour MP Diane Abbott’s words say it all: “Students in this country already learn about traditional figures such as Winston Churchill, Oliver Cromwell and Florence Nightingale. Mary Seacole is simply another such important individual. Not of less significance and certainly not expendable.”

This controversy is not just about falsification of history, but about a wilful ignorance that the contribution of one human being to the world can be different in value from that of another. The Labour MP Diane Abbott’s words say it all: “Students in this country already learn about traditional figures such as Winston Churchill, Oliver Cromwell and Florence Nightingale. Mary Seacole is simply another such important individual. Not of less significance and certainly not expendable.”

One day Diane Abbott could be a member of a Labour government.

I wonder who she will want booted out of the curriculum – Churchill, probably. (Ironically

Cromwell, another of the names she mentions as being of no more significance

than Seacole, currently has no place in the primary history curriculum and

schoolchildren already know more of Seacole than of him).

The best service primary History teachers can do is to teach

children to be questioning of motives – we already teach them that historical sources

vary in value, but we must also show them that modern politicians and modern

newspapers are ready to spin and twist facts in order to make the past fit into

their own view of the present.

Follow @7000hours